Guest blog on Risk Thinking

Dr. Ron Dembo is an academic, successful, entrepreneur and consultant to the some of the world’s largest corporations and banks. He has had a distinguished academic research career as a professor of Operations Research and Computer Science at Yale University and as well as a visiting professor at MIT.

He was the Founder and CEO of Algorithmics Incorporated, growing it organically from a startup to the world’s largest enterprise risk-management software company, with offices in fifteen countries, over 70% of the world’s top 100 banks as clients, and consistent recognition as one of Canada’s 50 best-managed companies. Algorithmics was sold to Fitch in 2005 and later to IBM in 2012.

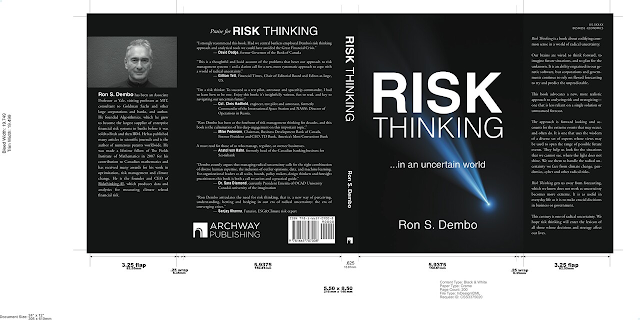

Risk Thinking is a book about codifying common sense in a world of radical uncertainty. Our brains are wired to think forward, to imagine future situations and to plan for the unknown. It’s an ability engrained in our genetic software but somehow lost in translation to a globalized society where corporations and governments depend on flawed forecasting to try and predict the unpredictable.

But the book is also far more than that. It advocates a new, more realistic approach to analyzing risk and strategizing for the future that is less dependent on the one simple solution or one un-nuanced forecast and takes into greater account the need for flexibility and diverse approaches.

In the past, if an earthquake shook the ground beneath our ancestors’ feet, our primitive huts slipped into the abyss. When the rains did not come, our crops failed. We learned to plan (hedge) for these events by storing grain in the good times because those who did not starved.

With our planning we sought mastery over nature – to beat it at its own randomized game. We industrialized, building machines that brought us in from our agrarian existence to cities risen from the wilderness. We began to need fewer and fewer hands to feed more and more mouths. We became billions, and we abandoned the earth around us. Trees became commodities; wildlife became exotic. That green and blue which once enveloped us became no more than a holiday destination.

With the advent of statistics and probability now taught at school, we grow more confident in our planning. Today our supply chains are cavernous and complex, our communication worldwide and instant, our industries automated, our economies immediately reactive, our politicians uninhibited, and our greed for consumable resources gargantuan and unimpeded. And we make bolder and bolder predictions with a straight face, genuinely believing in our capacity for foresight – convincing ourselves that we know what’s coming.

But there are events around every corner, ready to humble us: events that from infinitesimally small beginnings penetrate through our armor and tear our systems to shreds – the pandemics, financial crashes, cyberattacks, terrorist acts, geopolitical conflicts and man-made disasters.

As the world becomes more complicated, with nation-spanning corporations and worldwide financial webs, and as big data, machine learning, and artificial intelligence (AI) shift the decisions away from us, our vulnerability to radical uncertainty grows and forecasting is proven increasingly ineffective. There is simply too much we must model over systems hypersensitive to disruption and rapidly reactive.

Yet every day our governments and companies continue to try, despite their abysmal record of success. Our economists routinely get the forecasts they are paid to produce wrong by spectacular margins, and multi-billion-dollar businesses plan manufacturing processes that collapse dramatically when minute disruptions break into their lines.

This requires rewiring how we think about the future – a revision to the way we teach aspiring managers in our business schools to make decisions about risk. We must free ourselves from our addiction to forecasts, realising their ineptitude in the face of uncertainty. This book describes an alternative which we call ‘risk thinking’.

The risk thinker accepts that in a radically uncertain world we cannot ordain outcomes; we can only prepare ourselves for their potential occurrence. In our world, there is no single right or wrong answer to a question. There is only a multi-faceted strategy. It’s a better way of reasoning, and our building blocks are scenarios.

As we drive forward into a world of radical uncertainty, scenarios are our headlights in the dark. Just like headlights, they reach forward and capture a wide picture of the upcoming landscape as we navigate. More importantly, they only shine so far, and their beams fail to capture much of what is to the side of us. Objects ahead appear only as vague shapes in the distance at first, our headlights bouncing light onto them to reveal an outline, catch a movement, and cast unusual shadows. When something fuzzy comes into view, we might decide to slow down and place both hands on the steering wheel, providing ourselves greater time or maneuverability to react. Then, as we move forward and our beams of light become stronger, the object is illuminated more clearly, and we recognize it: a stray branch lying across the road or a child attempting to cross. Having been warned of the presence, we choose from a more informed, safer position: redirect or ignore (hedge or bet). That is the essence of the risk-thinking process and the scenario generation that supports it.

The metaphor of headlights in the dark lighting up our future works well for risk thinking. We can only illuminate a partial view of the future (the scenarios we generate). It is the scenarios we have ignored or missed that are the bets we are taking – the parts of the road we have left unlit with our headlights. So, in many cases of radical uncertainty, it behooves us to slow down (hedge) to be able to deal with the proverbial moose that will suddenly jump into view unexpectedly. Extending the metaphor, as we get closer to an object, our vision of it improves – just as in life, as we get closer to a future date, we often can improve our scenarios to better identify risk.

There is not a day that passes when I do not see some other example of the need for a formalized, science-based approach to risk, especially since we have moved into a much faster-paced, data- driven world where recent wisdom regarding how best to manage has been shattered by the clear fragility of our economic systems. There are many books written about the problem but little about the solution. What they and others really need is to adopt a codified, science- and mathematics-based method of analysis – risk thinking. This book reveals that method. And it is written for all of us who make decisions every day in the face of a radically uncertain future.

Comments

Post a Comment