The World Economic Forums - Global Risks Report - a must read

This is reproduced from the World Economic Forum launch page

The Global Risks Report (downloadable from here) explores some of the most severe risks we may face over the next decade, against a backdrop of rapid technological change, economic uncertainty, a warming planet and conflict. As cooperation comes under pressure, weakened economies and societies may only require the smallest shock to edge past the tipping point of resilience.

A deteriorating global outlook

Looking back at the events of

2023, plenty of developments captured the attention of people around the world

– while others received minimal scrutiny. Vulnerable populations grappled with

lethal conflicts, from Sudan to Gaza and Israel, alongside record-breaking heat

conditions, drought, wildfires and flooding. Societal discontent was palpable

in many countries, with news cycles dominated by polarization, violent

protests, riots and strikes. Although globally destabilizing consequences –

such as those seen at the initial outbreak of the Russia-Ukraine war or the

COVID-19 pandemic – were largely avoided, the longer-term outlook for these

developments could bring further global shocks.

As we enter 2024, 2023-2024 GRPS

results highlight a predominantly negative outlook for the world over the next

two years that is expected to worsen over the next decade (Figure A). Surveyed

in September 2023, the majority of respondents (54%) anticipate some

instability and a moderate risk of global catastrophes, while another 30%

expect even more turbulent conditions. The outlook is markedly more negative

over the 10-year time horizon, with nearly two-thirds of respondents expecting

a stormy or turbulent outlook.

Figure A:

In this year’s report, we contextualize our analysis through four structural forces that will shape the materialization and management of global risks over the next decade. These are longer-term shifts in the arrangement of and relationship between four systemic elements of the global landscape:

– Trajectories relating to global

warming and related consequences to Earth systems (Climate change).

– Changes in the size, growth and

structure of populations around the world (Demographic bifurcation).

– Developmental pathways for

frontier technologies (Technological acceleration).

– Material evolution in the

concentration and sources of geopolitical power (Geostrategic shifts).

A new set of global conditions is

taking shape across each of these domains and these transitions will be

characterized by uncertainty and volatility. As societies seek to adapt to

these changing forces, their capacity to prepare for and respond to global

risks will be affected.

Environmental risks could hit

the point of no return

Environmental risks continue to

dominate the risks landscape over all three time frames. Two-thirds of GRPS

respondents rank Extreme weather as the top risk most likely to present a

material crisis on a global scale in 2024 (Figure B), with the warming phase of

the El Niño-Southern Oscillation (ENSO) cycle projected to intensify and

persist until May this year. It is also seen as the second-most severe risk

over the two-year time frame and similar to last year’s rankings, nearly all

environmental risks feature among the top 10 over the longer term (Figure C).

Figure B:

Figure C:

However, GRPS respondents disagree about the urgency of environmental risks, in particular Biodiversity loss and ecosystem collapse and Critical change to Earth systems. Younger respondents tend to rank these risks far more highly over the two-year period compared to older age groups, with both risks featuring in their top 10 rankings in the short term. The private sector highlights these risks as top concerns over the longer term, in contrast to respondents from civil society or government who prioritize these risks over shorter time frames. This dissonance in perceptions of urgency among key decision-makers implies sub-optimal alignment and decision-making, heightening the risk of missing key moments of intervention, which would result in long-term changes to planetary systems.

Chapter 2.3: A 3◦C world explores

the consequences of passing at least one “climate tipping point” within the

next decade. Recent research suggests that the threshold for triggering

long-term, potentially irreversible and self-perpetuating changes to select

planetary systems is likely to be passed at or before 1.5◦C of global warming,

which is currently anticipated to be reached by the early 2030s. Many economies

will remain largely unprepared for “non-linear” impacts: the triggering of a

nexus of several related socioenvironmental risks has the potential to speed up

climate change, through the release of carbon emissions, and amplify related

impacts, threatening climate-vulnerable populations. The collective ability of

societies to adapt could be overwhelmed, considering the sheer scale of

potential impacts and infrastructure investment requirements, leaving some

communities and countries unable to absorb both the acute and chronic effects

of rapid climate change.

As polarization grows and

technological risks remain unchecked, ‘truth’ will come under pressure

Societal polarization features among the top three risks over both the current and two-year time horizons,

ranking #9 over the longer term. In addition, Societal polarization and

Economic downturn are seen as the most interconnected – and therefore influential

– risks in the global risks network (Figure D), as drivers and possible

consequences of numerous risks.

Figure D:

Emerging as the most severe global risk anticipated over the next two years, foreign and domestic actors alike will leverage Misinformation and disinformation to further widen societal and political divides (Chapter 1.3: False information). As close to three billion people are expected to head to the electoral polls across several economies – including Bangladesh, India, Indonesia, Mexico, Pakistan, the United Kingdom and the United States – over the next two years, the widespread use of misinformation and disinformation, and tools to disseminate it, may undermine the legitimacy of newly elected governments. Resulting unrest could range from violent protests and hate crimes to civil confrontation and terrorism.

Beyond elections, perceptions of

reality are likely to also become more polarized, infiltrating the public

discourse on issues ranging from public health to social justice. However, as

truth is undermined, the risk of domestic propaganda and censorship will also

rise in turn. In response to mis- and disinformation, governments could be

increasingly empowered to control information based on what they determine to

be “true”. Freedoms relating to the internet, press and access to wider sources

of information that are already in decline risk descending into broader

repression of information flows across a wider set of countries.

Economic strains on low- and

middle-income people – and countries – are set to grow

The Cost-of-living crisis remains

a major concern in the outlook for 2024 (Figure B). The economic risks of

Inflation (#7) and Economic downturn (#9) are also notable new entrants to the

top 10 risk rankings over the two-year period (Figure C). Although a “softer

landing” appears to be prevailing for now, the near-term outlook remains highly

uncertain. There are multiple sources of continued supply-side price pressures

looming over the next two years, from El Niño conditions to the potential

escalation of live conflicts. And if interest rates remain relatively high for

longer, small- and medium-sized enterprises and heavily indebted countries will

be particularly exposed to debt distress (Chapter 1.5: Economic uncertainty).

Economic uncertainty will weigh

heavily across most markets, but capital will be the costliest for the most

vulnerable countries. Climate-vulnerable or conflict-prone countries stand to

be increasingly locked out of much-needed digital and physical infrastructure,

trade and green investments and related economic opportunities. As the adaptive

capacities of these fragile states erodes further, related societal and

environmental impacts are amplified.

Similarly, the convergence of

technological advances and geopolitical dynamics will likely create a new set

of winners and losers across advanced and developing economies alike (Chapter

2.4: AI in charge). If commercial incentives and geopolitical imperatives,

rather than public interest, remain the primary drivers of the development of

artificial intelligence (AI) and other frontier technologies, the digital gap

between high- and low-income countries will drive a stark disparity in the

distribution of related benefits – and risks. Vulnerable countries and

communities would be left further behind, digitally isolated from turbocharged

AI breakthroughs impacting economic productivity, finance, climate, education

and healthcare, as well as related job creation.

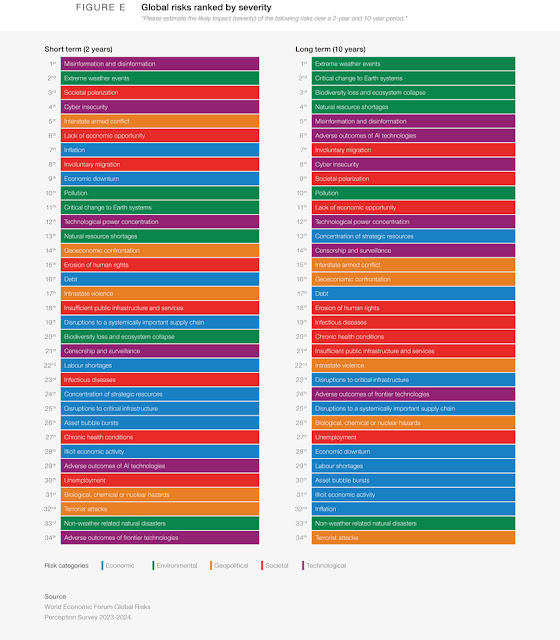

Over the longer term,

developmental progress and living standards are at risk. Economic,

environmental and technological trends are likely to entrench existing

challenges around labour and social mobility, blocking individuals from income

and skilling opportunities, and therefore the ability to improve economic

status (Chapter 2.5: End of development?). Lack of economic opportunity is a

top 10 risk over the two-year period, but is seemingly less of a concern for

global decision-makers over the longer-term horizon, dropping to #11 (Figure

E). High rates of job churn – both job creation and destruction – have the

potential to result in deeply bifurcated labour markets between and within

developed and developing economies. While the productivity benefits of these

economic transitions should not be underestimated, manufacturing- or

services-led export growth might no longer offer traditional pathways to

greater prosperity for developing countries.

The narrowing of individual

pathways to stable livelihoods would also impact metrics of human development –

from poverty to access to education and healthcare. Marked changes in the

social contract as intergenerational mobility declines would radically reshape

societal and political dynamics in both advanced and developing economies.

Simmering geopolitical

tensions combined with technology will drive new security risks

As both a product and driver of

state fragility, Interstate armed conflict is a new entrant into the top risk

rankings over the two-year horizon (Figure C). As the focus of major powers

becomes stretched across multiple fronts, conflict contagion is a key concern

(Chapter 1.4: Rise in conflict). There are several frozen conflicts at risk of

heating up in the near term, due to spillover threats or growing state

fragility.

This becomes an even more

worrying risk in the context of recent technological advances. In the absence

of concerted collaboration, a globally fragmented approach to regulating

frontier technologies is unlikely to prevent the spread of its most dangerous

capabilities and, in fact, may encourage proliferation (Chapter 2.4: AI in

charge). Over the longer-term, technological advances, including in generative

AI, will enable a range of non-state and state actors to access a superhuman

breadth of knowledge to conceptualize and develop new tools of disruption and

conflict, from malware to biological weapons.

In this environment, the lines

between the state, organized crime, private militia and terrorist groups would

blur further. A broad set of non-state actors will capitalize on weakened

systems, cementing the cycle between conflict, fragility, corruption and crime.

Illicit economic activity (#31) is one of the lowest-ranked risks over the

10-year period but is seen to be triggered by a number of the top-ranked risks

over the two- and 10-year horizons (Figure D). Economic hardship – combined

with technological advances, resource stress and conflict – is likely to push

more people towards crime, militarization or radicalization and contribute to

the globalization of organized crime in targets and operations (Chapter 2.6:

Crime wave).

The growing internationalization

of conflicts by a wider set of powers could lead to deadlier, prolonged warfare

and overwhelming humanitarian crises. With multiple states engaged in proxy,

and perhaps even direct warfare, incentives to condense decision time through

the integration of AI will grow. The creep of machine intelligence into

conflict decision-making – to autonomously select targets and determine

objectives – would significantly raise the risk of accidental or intentional

escalation over the next decade.

Ideological and geoeconomic divides will disrupt the future of governance

A deeper divide on the

international stage between multiple poles of power and between the Global

North and South would paralyze international governance mechanisms and divert

the attention and resources of major powers away from urgent global risks.

Asked about the global political

outlook for cooperation on risks over the next decade, two-thirds of GRPS

respondents feel that we will face a multipolar or fragmented order in which

middle and great powers contest, set and enforce regional rules and norms. Over

the next decade, as dissatisfaction with the continued dominance of the Global

North grows, an evolving set of states will seek a more pivotal influence on

the global stage across multiple domains, asserting their power in military,

technological and economic terms.

As states in the Global South

bear the brunt of a changing climate, the aftereffects of pandemic-era crises

and geoeconomic rifts between major powers, growing alignment and political

alliances within this historically disparate group of countries could increasingly

shape security dynamics, including implications for high-stakes hotspots: the

Russia-Ukraine war, the Middle East conflict and tensions over Taiwan (Chapter

1.4: Rise in conflict). Coordinated efforts to isolate “rogue” states are

likely to be increasingly futile, while international governance and

peacekeeping efforts shown to be ineffective at “policing” conflict could be

sidelined.

The shifting balance of influence

in global affairs is particularly evident in the internationalization of

conflicts – where pivotal powers will increasingly lend support and resources

to garner political allies – but will also shape the longer-term trajectory and

management of global risks more broadly. For example, access to highly

concentrated tech stacks will become an even more critical component of soft

power for major powers to cement their influence. However, other countries with

competitive advantages in upstream value chains – from critical minerals to

high-value IP and capital – will likely leverage these economic assets to

obtain access to advanced technologies, leading to novel power dynamics.

Opportunities for action to

address global risks in a fragmented world

Cooperation will come under

pressure in this fragmented, in-flux world. However there remain key

opportunities for action that can be taken locally or internationally,

individually or collaboratively – that can significantly reduce the impact of

global risks.

Localized strategies leveraging

investment and regulation can reduce the impact of those inevitable risks that

we can prepare for, and both the public and private sector can play a key role

to extend these benefits to all. Single breakthrough endeavors, grown through

efforts to prioritize the future and focus on research and development, can

similarly help make the world a safer place. The collective actions of

individual citizens, companies and countries may seem insignificant on their

own, but at critical mass they can move the needle on global risk reduction.

Finally, even in a world that is increasingly fragmented, cross-border

collaboration at scale remains critical for risks that are decisive for human

security and prosperity.

The next decade will usher in a

period of significant change, stretching our adaptive capacity to the limit. A

multiplicity of entirely different futures is conceivable over this time frame,

and a more positive path can be shaped through our actions to address global

risks today.

Comments

Post a Comment