The Convention on Biological Diversity. Does it live in a parallel world?

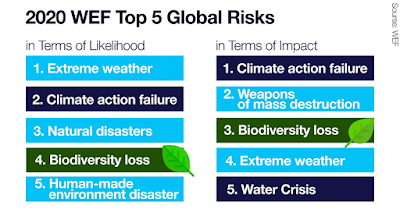

With the World Economic Forum (WEF) just started I thought id share the WEF top five global risks. As they are all related to the Sustainable Development Goals (SDGs) .

In

Rio in 1992 the Earth Summit agreed two conventions – on climate change and

biodiversity. It was also the birth place for what became a series of other

legal agreements the:

- Desertification Convention,

- Straddling Fish Stocks Agreement,

- Persistent and Organic Pollutants agreement, and

- Prior Informed Consent agreement.

As

some of you know this year, we will have two very important Conferences of the

Parties (COP). These are the two Rio

Conventions.

The

UNFCCC COP will be in Glasgow to review the progress towards the Paris Climate

commitments and to hopefully ratchet up to higher commitments. I will write

about the Glasgow UNFCCC on another occasion and my frustration with the

political action.

The

second COP that of the Convention on Biological Diversity will meet in October

in Kunming, China to set new Biodiversity Goals and Targets.

To

refresh the reader the 2020 Aichi Biodiversity

Targets

were originally set in Nagoya COP in 2010 and hybrid versions of them were

adopted as part of the Sustainable Development Goals (SDGs) in 2015.

It

has become increasingly clear over the last year, even to the general public,

that we have a huge crisis both in dealing with stopping climate change and in

reversing the extinction of species.

Since

1992 a huge amount of work has been put in to ensure that we have the

scientific evidence that these are critical issues. In both cases the science

has warned us what was happening and the politicians have not heeded those

warnings to the level that was clearly needed. If anything, the scientists

under-estimated the changes that were happening. The politicians have

consistently underperformed assuming the problems would not fall into their

time in power and so why put the extra effort in.

This

article is focusing on what has now been released the Zero draft of the

Post-2020 Global Biodiversity Framework. A vital step towards governments

agreeing a set of targets and goals up to 2050 with interim targets by 2030 to

keep them in line with the SDG timeline. By the way the choice of 2050 might

preempt governments to think about the post 2030 goals and targets being also

to 2050. Overall let me say it’s a good document and under the leadership of

Elizabeth Maruma Mrema, the Acting Executive Secretary the secretariat is in

very good hands. Of course the ambition isn’t to the level that it should be

but that often is the case with a zero draft.

Goals

and Targets

First,

it's good to ground what we mean by goals and targets and for that matter

indicators as too often they are mixed up. Goals describe what you want to

accomplish, a target is the numerical value that you want to improve by and an

indicator is something that helps you understand where you are in delivering

the target and allows you to measure your delivery of a target.

Theory of Change

Theory of Change

The

decision to have a theory of change approach is a very important development in

the context of developing policy. This has been sorely missed I would argue

since the 1992 Rio Earth Summit.

The

proposed framework being put forward to help deliver the goals has a very

similar approach to Agenda 21.

Agenda

21’s biodiversity chapter had a structure of

·

Basis

for Action

·

Objectives

(Goals)

·

Activities

o

Management-related

activities

o

Data

and information

o

International

and regional cooperation and coordination

·

Means

of Implementation

o

Financing

and cost evaluation

o

Scientific

and technological means

o

Human

resource development

o

Capacity-building

It’s

difficult to think of another UN negotiated text where this has happened. There

had been an attempt by G77 during the SDG negotiations to do something similar

under each goal. These targets became the alphabet targets but were not uniform

in the approach to what they needed to address.

In

the proposed framework for the 2030-2050 is:

·

2050

Vision

·

2030

and 2050 Goals

·

2030

Mission

·

2030

action targets

o

Reducing

threats to biodiversity

o

Meeting

people’s needs through sustainable use and benefit-sharing

o

Tools

and solutions for implementation and mainstreaming

·

Implementation

support mechanisms

·

Enabling

conditions

·

Responsibility

and transparency

·

Outreach,

awareness and uptake

For

Agenda 21 the UN secretariat was asked to estimate how much it would cost to

implement each of the chapters of Agenda 21. So, one of the critical missing

sections in the zero draft is on financing and cost evaluation. Let us just

review the 1992 Agenda 21 Biodiversity chapter text said on this:

“Conference secretariat has estimated the average total annual cost

(1993-2000) of implementing the activities of this chapter to be about $3.5

billion, including about $1.75 billion from the international community on

grant or concessional terms. These are indicative and order-of-magnitude

estimates only and have not been reviewed by Governments. Actual costs and

financial terms, including any that are non-concessional, will depend upon,

inter alia, the specific strategies and programmes Governments decide upon for

implementation.” (Agenda 21, 1992)

One of the problems with the SDGs is

that we also didn’t have an analysis of what the funding for each goal/target

might be and where that money might come from. It had been hoped that the

Financing for Development process might do that for each goal, but it did not.

In the follow up process to Agenda

21 the newly established UN Commission on Sustainable Development had as its

responsibilities in its first ten years that of reviewing governments

commitments to these funding targets. This ultimately at Rio+5 (1997) became a

reason why governments in the run up to the 2002 World Summit on Sustainable

Development increased ODA as it was clear that it was going down not

increasing. Something like this needs to happen at the CBD and for that matter

for the SDGs.

Drivers

of change

Again,

it was refreshing to see some of the key drivers of change being identified –

these are not new and formed the basis of the backdrop to the Rio+20 conference

in 2012 but worth underlining here they are:

·

Population

·

Urbanization

·

Resource

demand

In

addition, the impacts of climate – all of these have also been part of the

Nexus discussions on food-energy-water. Recognition of drivers enables

approaches to those drivers to be identified and action taken.

The

2030 Agenda for Sustainable Development and the CBD

This

is where a have a problem. For those reading this blog/article that have

followed the issue since I first raised it in a paper in November 2017, they

will know my concerns ones which I raised again in 2018 and in 2019 as did WWF in 2019.

One

of the serious concerns that both papers raise is that of creating two

different processes and by doing so reducing the political focus on the

biodiversity targets. At this point there is no attempt to link the suggested

targets to the SDGs. Will this create a parallel world where the biodiversity

community lives and will it massively reduce the political will to address

these huge issues as environment departments in governments are very weak. The

SDG agenda requires joined up government thinking and policy development – the

biodiversity community may be opting out of that and there is a huge chance

that will imapct on the delivery of these new proposed taregts.

There are twenty three targets in the SDGs that fall

either in 2020 or 2025. The paper I did with Prof Jamie Bartram and Gastón

Ocampo suggested four options for addressing how to integrate or not any new

targets.

Options

Analysis

From that paper:

Identifying

a future course of action for each affected target will depend in part on

SDG-wide policies and approaches; and in part on target-specific context, such

as the existence of a treaty or other process.

Alignment between these two influences will vary target-by-target.

One of us

(FD) consulted the UN Agencies and Programmes listed in Table 2 and presented an earlier version of this table to the

government Friends of Governance for Sustainable Development (FGSD, 2017) workshop on November 2nd

2017 (updated in 2018 and 2019)

to solicit their thinking on what to do with the affected targets. The

four-principal option-types, there and associated principal advantages and

disadvantages, and target-specific options described here are synthesized from

that process.

Option 1: That no updated

targets will be added to the SDGs to replace those that have expired and

monitoring and reporting will conclude at the date of the target.

Pros: The agreement on the SDGs and their

targets was one that had balanced the interests of all member states and

reopening this could cause that balance to be fractured

Cons: Some of the targets will be updated by

other forums and so then there will be refection of progress reported to the

HLPF in line with the new target. This will be particularly relevant to the CBD

and SAICM targets.

Option 2: That no updated

targets will be added to the SDGs to replace those that have fallen but there

will be continued monitoring of the

indicators, and reporting on progress if the target conditions have not been

achieved.

Pros: the agreement on the SDGs and their

targets was one that had balanced the interests of all member states and

reopening this could cause that balance to be fractured. It also allows

reporting on the targets even if other forums have changed them

Cons: These not updated targets will not have

been absorbed into the SDG targets and so it creates two classes of targets.

One which is in the SDGs and one that isn’t. In particular this is true for the

CBD and SAICM targets. It may impact on the level of commitment to the new

targets if they are not absorbed into the SDGs

Option 3: Any updated target

would need to be agreed through the UN General Assembly if it was to replace an

expiring target.

Pros: This option recognizes that the UN

General Assembly had agreed the SDGs and their targets so is the only ‘official

body’ that can update them

Cons: This could see the whole agreement

reopen unless member states agree to recognize the agreements made in other

forums. This still doesn’t address the targets that do not have other forums to

set new targets. In these cases, option 2 could continue

Option 4: That any updated

target agreed by a relevant UN body substitutes the old target without going

through renegotiation in the UN General Assembly. Where there is no

authoritative UN body then it is done through the UN General Assembly.

Pros: This would address all of the targets

that are going to finish in 2020 and 2025

Cons: This would open up the SDG targets

negotiations to Committee 2 of the UNGA to address those that have no plans to

be replaced and this could be a difficult negotiation

Final thoughts

In most cases, there are processes that will recommend continuation, modification, abandonment or

replacement of expiring targets such as the CBD and SAICM.

The real problem with this is if this is outside the SDG machinery, I strongly

believe that we will see the emergence of two classes of targets and ultimately

indicators.

This has the potential to threaten the overall cohesion of the SDG

enterprise and as crisis on Infinite Earths, which by the way has just finished

on CW TV. Do we really at this critical time for both biodiversity and climate

want to take the chance that we are creative different chances to move to an

integrated sustainable path for all of us?

Comments

Post a Comment